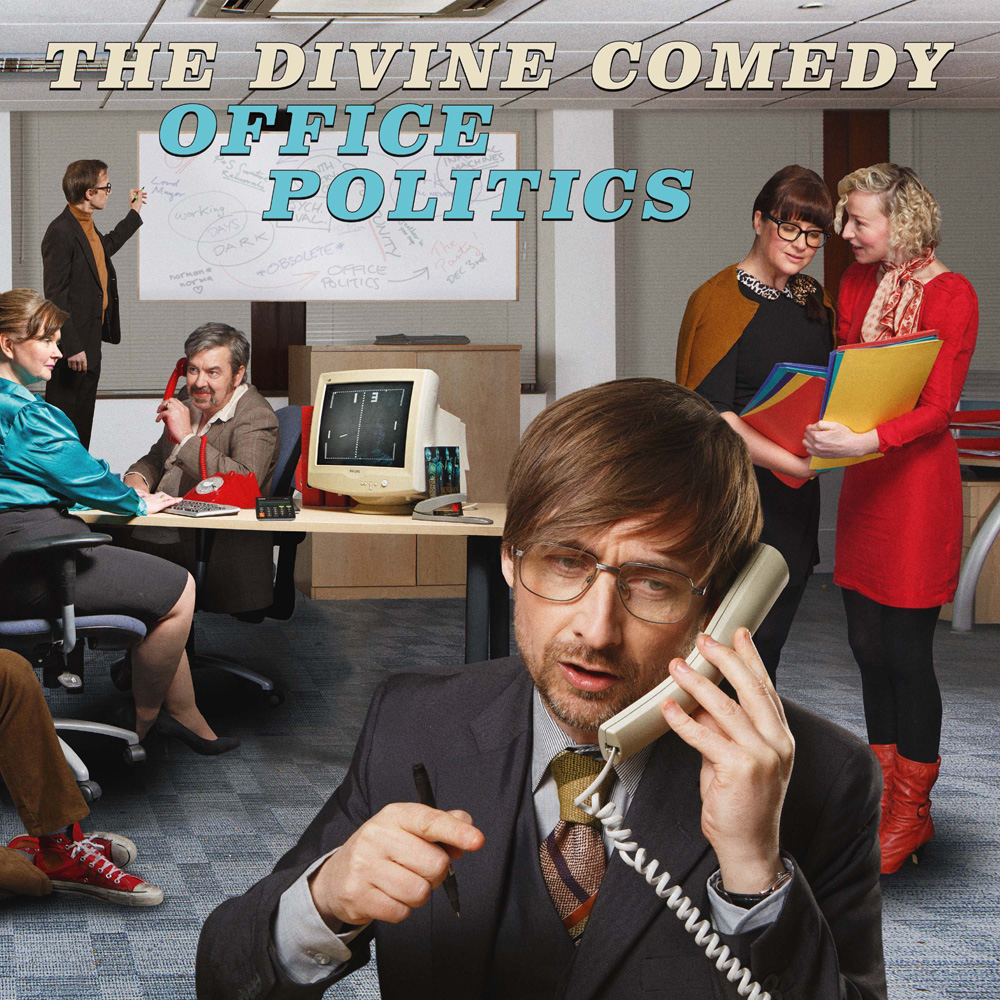

The Divine Comedy - Office Politics (Divine Comedy Records, 2019)

“The central characters in Office Politics are the machines. Machines that do this, machines that do that. Machines that will smother us all in our sleep.”

On June 7th 2019, The Divine Comedy return with a record that was very much made for these times. Office Politics comes three years after Foreverland, an album which saw Neil Hannon and his rejuvenated band of co-travellers enjoy their highest ever chart placing (UK #7, Mojo Top 50 albums 2016). It’s a record steeped in ambivalence about the depersonalised nature of the human experience; a record populated by beleaguered ghosts who wandered into the machine of modern life without quite knowing how to get out of it again. But it’s also, for all the new synth textures and machine-tooled pop deviations, unmistakably a Divine Comedy album – endowed with all the heart, humour and hooks that fans have come to associate with the source of hits such as Something For The Weekend, Everybody Knows (Except You), National Express and Come Home Billy Bird.

Ask Neil Hannon about the overarching themes of his twelfth album, and he sounds less like the person who created the record and more like the first person who happened to hear it. “It felt,” he says, “like the songs and the characters in it emerged faster than I could keep track of them.” Included among those characters are beleaguered banker and star of the title track, Sir Hillary Oldmoney, who “recalls the days/You could use your position to get your way”, and the eponymous star of Opportunity Knox who, in his zeal to attain a promotion, contrives to bump off the star of a previous Divine Comedy song (no spoilers here).

One of the first songs to appear fully formed on Office Politics – in the process, shining the anglepoise on the space where many more would follow – was Absolutely Obsolete. Featuring guest turns from singer-songwriter (and Neil’s partner) Cathy Davey, Chris Difford (Squeeze) and Thomas Walsh (Pugwash, The Duckworth Lewis Method) the song zones in on the idea that “we’re all living in this zero-hours world, where your identity is no longer bound up with your lifetime vocation, because there are no lifetime vocations any more!” Built around a sample taken from Percy Faith & His Orchestra’s Bim! Bam!! Boom!!!, the murky Latin syncopations of You’ll Never Work In This Town Again drill down into the contradiction between the desire for automation and the unemployment in which it results.

On the face of it, there’s little to connect those songs to Dark Days Are Here Again – a song which took shape on the morning Hannon awoke to the news that Donald Trump was the new American President. “We were on tour in France, and the sky above was this apocalyptic metallic grey. Not only did it feel like the end of the world, but it looked like it too.” Similarly, there’s nothing to connect that song to the track which opens the album. “I don’t have to play by the usual rules” sings Neil on Queuejumper, a song inspired by a near-miss on the M4 in Ireland with a speeding BMW. In a world of tiered “experiences”, fast-track options and express lanes, the teasing chorus of “I jumped the queue/I jumped the queue cos I’m better than you,” locates a perfectly Hannonesque midpoint between exasperation and fatalism.

And yet, somehow taken as a whole, all the songs are vital details in a composite picture of a world where progress no longer appears to be serving our best interests. Coasting along to an irresistible electronic glam shuffle, Infernal Machines sees Hannon impassively itemising the automata to which we’ve outsourced almost every aspect of our lives. On Psychological Evaluation, we even find our protagonist on the analyst’s couch fielding questions from a inquisitive interface (“Dreams?/Oh, the usual/Hanging from high places or lingering in endless post office queues/Diet?/Brown) While the scenery and sentiments may shift from one song to the next, the common thread is Hannon’s palpable empathy for the characters that populate these songs. It’s a quality foregrounded by some of the most affecting moments on Office Politics. With an exquisite arrangement recorded live at the legendary Air Studios, I’m A Stranger Here sees its protagonist left all but exiled by the very innovations that are supposed to expedite a more harmonious day-to-day life.

Both on this song and on When The Working Day Is Done, the emotional centre of gravity is one and the same – and it often lies with the challenges faced by the characters about whom Hannon chooses to sing. Recalling the hypnotic orchestral grandeur of The Divine Comedy’s 1994 album Promenade, the latter song alchemises the commute home into an existential crie de coeur. “I’m lucky in so many ways,” says Neil, “I don’t have to sit on a crammed tube train twice a day, but I’ve done it enough to understand why people have disengage when descending that crowded escalator. Even as a kid, when I watched The Fall & Rise of Reginald Perrin, I wondered how you manage that.”

Of course, it wouldn’t be a Divine Comedy album if, among the moments of tender disclosure, there wasn’t also a scattering of outright whimsy. Synthesiser Service Centre Super Summer Sale took shape in the middle of the last Divine Comedy tour, during a day off in the Italian Alps. “I had two phrases written down in my notebook,” explains Neil, “One was ‘synthesiser service centre’ and the other was ‘super summer sale’. So obviously, I joined them together and the rest took care of itself.” On the album’s other “ad break” moment, Neil imagines what Philip Glass and Steve Reich might come up with if tasked with the job of creating a theme tune for a sit-com called Philip & Steve’s Furniture Removal Company. In its own way, this song is one of the most remarkable pieces of music bearing The Divine Comedy imprint, spidering out from a simple voice memo into a stirring climax, blown into the blue by a full-pelt choral finale.

A process that began with a non-specific feeling about the nature of modern life ended late in 2018 when Neil Hannon looked at the songs he had and realised that one song was needed to complete the emotional picture. Once again, eschewing the traditional instrumentation of previous Divine Comedy albums, he drew on fossilised fragments of “failed love affairs” to write A Feather In Your Cap – a bruised farewell to a former paramour whose DNA suggests more than a few turntable miles in the company of Behaviour-era Pet Shop Boys. “It was recorded the day after I submitted the finished album to my manager,” recalls Neil, “But, of course, the good thing about being signed to your own label is that you can do that sort of thing.”

Now on the verge of completing his third full decade as a recording artist, Neil says he has resigned himself to the fact that he’ll “probably always feel like a competition winner doing this for a living.” Talking about the period in the mid-90s that saw The Divine Comedy’s third album Casanova briefly confer pop stardom upon him, he says he feels “it was one of those eras that accidentally let some interesting people into mainstream media.” The fame was fun, but the main thing, he adds, is “the time, goodwill and freedom it bought me.” It’s a freedom that, in recent years, Neil Hannon has been determined not to squander. Along with Office Politics, he’s been working with Graham Linehan and Arthur Matthews on their musical adaptation of Father Ted – the classic Channel 4 sitcom for which Hannon’s Songs of Love was used as the theme music. Included on the Deluxe CD and Deluxe Digital editions of Office Politics will be Swallows and Amazons – The Original Piano Demos, an album comprising Hannon’s original demos for the acclaimed musical adaptation of Arthur Ransome’s 1930 novel.

“For better or for worse,” he says, “My identity is totally intertwined with my work. In that sense, I’m like a lot of the characters I sing about on this record. But unlike those characters, I can’t think of anything else I’d rather be doing.” For those of us who have followed The Divine Comedy’s story this far, it’s also hard to think of anything we’d rather he was doing.

Neil Hannon, The Divine Comedy (photo: press)