German label Ostinato Records is reviving the music of the Iftin Band, which has been gathering dust on cassette shelves in Somalia.

Mogadishu, 1986. Crystal blue Indian Ocean waters frothing and foaming along the longest coastline in continental Africa. White soft sand beaches and architecture reminiscent of this ancient part of the world’s place as a crossroads where Asia, Africa, and Europe begin and end. A white sheen on most buildings that made the city worthy of its pearly reputation.

The seafood? Fresh and exquisite. The music? Sweet as a broken date. The centerpiece?

The Al-Curuuba (Al-Uruba) hotel, the cream of abodes along East Africa’s Indian Ocean coast. Situated on the picturesque Lido Beach, adjacent to Mogadishu’s iconic lighthouse, the s-shaped hotel was draped with Arabesque and Somali aesthetics and had it all—studded suites, restaurants, ballrooms, a nightclub, a beach club, a well stocked bar for all persuasions, and a lesser known makeshift recording studio.

But Al-Uruba’s club, like the haunts of other luxury Mogadishu hotels—Shabelle, Jazira, and Juuba—was not for everyone. Entrance fees were exorbitant, an exclusive affair. Many couldn’t hear bands in full swing at Al-Uruba’s nightclub, opting instead for the more democratic, free of charge national theater. Operating at both Al-Uruba and the national theater was Iftin Band, the raucous, brass-heavy, electric, smoldering, world class outfit that, in the early 1980s, broke away from Somalia’s ministry of education, an academy of musical talent, and

blessed every song on this retrospective.

Iftin inebriated a global audience at Al-Uruba while cooking new tracks on the fly on the national theater’s bottom floor, just below the main stage for plays. This compilation reveals the recording sessions at Al-Uruba while making room for the ever important soundtracks to Riwaayads (theater plays).

From Mogadishu to around the world

Going private gave them the space to experiment and learn a great deal by simply taking requests from guests at Al-Uruba’s nightclub. The tourists, business travelers, and government workers were in town from across Africa and Asia, alongside western countries. Demand for dance music from the world over internationalized Iftin’s sound, already formed on a cosmopolitan foundation of Somali music, owing to the Somali coast’s role as a brisk Indian Ocean trading hub for centuries. Americans in town? Fire up James Brown. Travelers from Lagos? Dust off the Afrobeat repertoire. Kenyans? It’s going to be a Benga guitar kind of night. These parties were energized by Banaadiri rhythms of Somalia’s south.

As a private band, Iftin needed a private supplier of the latest instruments and technology. Enter the co-producer of this record, Ahmed Sharif, whose family ran an import business and financed private shows and concerts. Sharif’s family delivered Iftin the tools they needed and fronted funding for many of their performances.

Recordings found reveal diverse inspirations and roots of Somali styles

Those shows, like this entire Somali music era, were led by women. Their unrivaled talent coupled with women empowerment policies yielded a vast roster of women singers, the captains of Somalia’s cherished cultural era. And they were treated with immense dignity. Iftin offered paid maternity leave and the government sent a special police task force to protect them.

Some of these recordings found their way to Shankarphone, a shop set up by founder, Shankar, that outcompeted rivals. Lines would stretch through Mogadishu’s largest market to secure the latest Iftin cassettes. After the civil war broke out in the early 1990s, those cassettes made their way around the world, leading to a seven year journey to locate the finest recordings and the performing artists on each track.

Digitized and compiled from cassettes sourced from London, Djibouti, Mogadishu, Nairobi, and Dubai, this is the first official compilation of Somalia’s most venerated band, encapsulating a memory when Somali musicians were operating a class apart from many of their contemporaries.

“Iftin wasn’t a band,” says lead singer Sitey Xosul Wanaag, “it was a vision.”

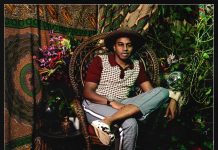

NMR (photo: press Iftin Band)